We experience the world through the interplay of our perceptions and actions. What we can or cannot perceive, what we can or cannot do, shapes the ways in which we engage with and what we experience as reality. Our experience of this reality reflects our abilities. We may have needs, desires, seeking to satisfy them somehow, but without knowledge, without abilities, we have no clue how to direct our activities to fulfill these wants. These abilities are the result of hard work, a long process of learning and cultivation, and can change through additional learning and hard work.

If I go into a forest expecting to find something to eat, I must be able for example to differentiate edible plants from the rest, my senses tell them apart from among the rest. It is this ability, acquired through prior trial and error, through apprenticeship and training, that reveals these plants to my eyes, my hands, my nose, my mouth, as edible.

If instead I go into a grocery store, a different constellation of abilities is necessary: I need to read labels off packages, know what these labels refer to, how tasty and nutritious the packaged contents might be, and I need to know how to pay. This might seem trivial after we get the hang of it, but don’t we remember, as kids we were taught how to purchase things, and we come across the learning phase even as adults, when we go to a foreign country or when new products or novel ways for paying appear.

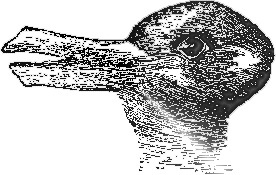

For us to experience, to perceive and act, we must be able to discern and foreground specific features of reality, while backgrounding others. To illustrate this point, I have found what is referred to as “gestalt pictures” very helpful.

We see the picture on the left as either a rabbit (ears pointing left) or as a duck (beak pointing left). We have been taught to recognize rabbits and ducks, and we switch between viewing the picture as either. But what if we did not know about ducks? If we had never seen one, in flesh or in picture, and nobody had taught us to recognize it? If we only knew about rabbits, it would be only a rabbit that we could possibly see in the picture, it would be the only thing we would recognize.

We see the picture on the left as either a rabbit (ears pointing left) or as a duck (beak pointing left). We have been taught to recognize rabbits and ducks, and we switch between viewing the picture as either. But what if we did not know about ducks? If we had never seen one, in flesh or in picture, and nobody had taught us to recognize it? If we only knew about rabbits, it would be only a rabbit that we could possibly see in the picture, it would be the only thing we would recognize.

Similarly, on the left, we see a tree with birds flying over it; but we can also see – if we switch foreground and background – a gorilla and a lion. Again, if we had not been taught to recognize gorillas or lions, we could not possibly see them in the picture. The range of our perceptions is limited by our knowledge.

We all become acutely aware of this dependence of our experience of the world on our abilities whenever we learn something new. For example, with a new language, when we slowly learn to recognize the script and the sounds and comprehend them as meaningful text and utterances. When we learn how to use a new tool, how to hold it, what sound it makes when used properly or improperly. Or when we taste a new dish or drink, learning to distinguish the different flavors.