During my years in Baltimore, I worked with several Chinese and Japanese colleagues, and we frequently went to eat together at Chinese restaurants – the greater Baltimore area has several excellent ones. We always shared dishes, whether whole entrées, or dim-sum, small plates with 3-4 pieces of delicacies – dumplings of all sorts and shapes, steamed or fried, sweet and savory cakes, stuffed buns, rice wrapped in lotus leaves, and so much more. To properly eat Chinese food one has to use chopsticks, which I had never really used before. With communally shared food, to manage to feed oneself requires efficient use of eating utensils, and my friends found this a great motivation for me to learn how to use chopsticks.

When I began my tries at holding a pair of chopsticks, my fingers did not know what to feel for, what was relevant for the hold and what not. When trying to imitate how my friends were holding their chopsticks, my eyes did not know what to look for, to see the important part of the hold and ignore the unimportant. I tried to copy the way my friends held their chopsticks, my eyes looking at their fingers, then at mine, adjusting, registering what my fingers felt, then try to use. Reach to grab a dumpling with the chopstick tips, use the tips to tear a piece of cake, try to bring the piece over to my mouth, registering what my eyes saw, what fingers felt. Sometimes I held the chopsticks too close to their tips, sometimes they were not stable enough and the morsel of food would fall off, sometimes too stable and could not open to grab. Amidst my friends’ mirth and guidance, there was a clear criterion for whether I had learned how to use chopsticks: could I feed myself? could I grab a piece of food and bring it from the plate to my mouth? For the first few outings I did go a bit hungry, but eventually I began to get a feel for holding the chopsticks, one always held stable, the other mobile, controlled by the thumb and index finger. My fingers learned to recognize the chopsticks, adjust them, coordinate with my eyes. And with practice I got better and better, and now can comfortably hold and use different kind and size chopsticks, long, short, thick, thin, very thin, wooden or plastic or even metal ones.

It is through such trial and error processes that we develop abilities, learn, acquire knowledge. Sensations – from the eyes and fingers in the case of the chopsticks – come together with muscle movements (hand and fingers). Muscle movements and their effects on the world result in a change in sensations, adjustment of muscle movements, and this back and forth continues, until a goal is reached – in the case of the chopsticks, get to grab a piece of food, get the food into the mouth. This trial and error process brings together our body and the world, and as the back and forth of sensory input and muscle output goes on, our sensations are organized into perception of objects and our movements into discernible actions directed toward these objects. The objects we perceive in the world emerge through the feedback provided by the results of our actions. An important feature of this trial and error process is that the more we do, the better we become at doing, at integrating perception and action. Practice makes perfect.

This is also how we begin to learn a language, through a trial and error process, under someone’s guidance, pointing at the world, hearing a sound, vocalizing (moving lips, jaws, tongue, vocal cords), hearing our own sound and receiving feedback from our guide as well. And in this way we organize our perception of the world into objects, objects we associate with specific sounds, and it is an organization compatible with that of our guides and teachers.

With trial and error, we learn and develop abilities on our own, by engaging with the world on our own, but also by copying others (sometimes even animals). We also learn through socialization, under the guidance of others. We learn because we may be driven to satisfy a need (eat or drink), be praised by a tutor, feel good about mastering something, or we could be just playing, getting our senses and muscles to work together.

We are all of course intimately familiar with what I have written above, with how we develop abilities, how we acquire knowledge, how we link our perceptions and actions. We do it all the time, but usually we do not spend much time reflecting and thinking about it. But our knowledge, our abilities, provide the basis for our experience of the world, how we perceive and act.

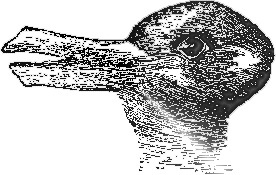

We see the picture on the left as either a rabbit (ears pointing left) or as a duck (beak pointing left). We have been taught to recognize rabbits and ducks, and we switch between viewing the picture as either. But what if we did not know about ducks? If we had never seen one, in flesh or in picture, and nobody had taught us to recognize it? If we only knew about rabbits, it would be only a rabbit that we could possibly see in the picture, it would be the only thing we would recognize.

We see the picture on the left as either a rabbit (ears pointing left) or as a duck (beak pointing left). We have been taught to recognize rabbits and ducks, and we switch between viewing the picture as either. But what if we did not know about ducks? If we had never seen one, in flesh or in picture, and nobody had taught us to recognize it? If we only knew about rabbits, it would be only a rabbit that we could possibly see in the picture, it would be the only thing we would recognize.