The way we experience the world reflects very closely the way we are. What we are, what we bring along with us to our encounters with reality, gives form and meaning to our experience.

A lot of people I have talked with will readily agree with this view. Very frequently, they will go on to say that it is the beliefs and principles we have that shape our perceptions, that provide us with a sense of who we are and what our goals are, that orient us in the world and guide our actions. It is these that we bring along with us, they would say, that define essentially who we are, and give rise to the differences in our experiences.

We are all fairly familiar with the inadequacies and limitations of beliefs and principles for describing ourselves and our experiences. When we are confronted with experiences that contradict our beliefs we find ways to push these experiences aside, sweep them under the rug as it is, keeping what we describe as our beliefs intact. And oh so many times we act contrary to our principles…

Beliefs and principles are abstractions of course, too crude to capture our concrete attitudes and patterns of behavior in all their diversity and mutability. Sometimes, they may be adequate as a communication shorthand, but they are not very helpful for approaching the basis of our perceptions and our conduct, how we experience the world. I think it is more helpful to look instead at concrete patterns of behavior, and the experiences associated with them.

For example, we taste and smell food and drink before we fully consume it – and if we cannot tell whether it is spoiled or contaminated we might get into trouble. If we know enough, plants and mushrooms in the fields appear to us as food, medicine, building material, this and that or the other. But if we do not know enough, they are all an undifferentiated jumble, which we approach without any expectation or means to obtain food, medicine or anything else.

In an urban setting, driving, the physical act of driving, encompasses among many other things knowledge about the car itself, about the road conditions, observing signs for lanes, stops, warnings, as well as monitoring, predicting and reacting to other drivers’ behavior. Successful driving hinges on the continuous congruence between our expectations, our actions, and what actually happens.

Along the same lines, our experience of interacting socially with each other is shaped by the clothes one wears, their skin color, gender, accent, manners, and so on. We use such cues to place someone, develop a sense of what our interaction might be like, what we might want it to be like, and we conduct ourselves accordingly. Some of these cues we may consider very important, some not as much. We differ of course which ones we pay more or less attention to; and of course there are aspects of someone’s appearance or behavior we might be oblivious to, not accustomed to noticing. It is interesting to note that we often get quite uncomfortable if we have misplaced or cannot place someone, we get confused or even angry – we might get quite upset, for example, if we cannot readily tell someone’s gender.

The knowledge, the abilities through which we experience the world, perceive and act, do not derive from beliefs and principles. Beliefs and principles are abstractions that only point to these abilities of ours. The abilities themselves however are the result of learning, reinforcement, and refinement through years of socialization in our cultural milieu.

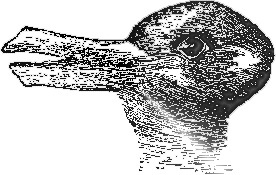

We see the picture on the left as either a rabbit (ears pointing left) or as a duck (beak pointing left). We have been taught to recognize rabbits and ducks, and we switch between viewing the picture as either. But what if we did not know about ducks? If we had never seen one, in flesh or in picture, and nobody had taught us to recognize it? If we only knew about rabbits, it would be only a rabbit that we could possibly see in the picture, it would be the only thing we would recognize.

We see the picture on the left as either a rabbit (ears pointing left) or as a duck (beak pointing left). We have been taught to recognize rabbits and ducks, and we switch between viewing the picture as either. But what if we did not know about ducks? If we had never seen one, in flesh or in picture, and nobody had taught us to recognize it? If we only knew about rabbits, it would be only a rabbit that we could possibly see in the picture, it would be the only thing we would recognize.